The Polaroid camera clicked, and Keith Schafer peeled back the negative to reveal another oscilloscope trace of an engine's heartbeat, black and white and frozen in time. It was the late 1980s, and this was cutting-edge condition monitoring: no digital storage, no cloud databases, just endless catalogs of photographs that Schafer would compare by hand, looking for patterns that signaled trouble brewing inside massive reciprocating engines.

"I kind of looked at it like a prospector panning for gold," Schafer recalls of his early days as an equipment analyst. "I'd hook up that engine analyzer, and I really didn't know what I was going to find. But I wanted to find it before anybody else knew it was there."

That prospector's mentality of curiosity, patience, and determination would define Keith Schafer's 40-year career in the natural gas pipeline industry. In that time, he transformed his facility’s practices from reactive firefighting to predictive precision maintenance. Now retired from TC Energy and spending his days riding motorcycles through West Virginia's Appalachian mountains, Schafer's journey from a entry-level mechanic to an industry thought leader offers valuable lessons for today's reliability professionals.

Building Blocks: From Index Cards to Engine Analyzers

Schafer's entry into compressor stations came naturally. His grandfather started laying natural gas pipeline in the early 1900s, and his father spent a career as a pipeliner. When Schafer was hired full-time in 1977, he initially wanted to be out on the pipeline. "But after a short time, I saw how fascinating the engines were that were pumping gas from station to station across the country."

The maintenance system he found would be unrecognizable today. The lead mechanic managed all preventive maintenance using a collection of three-by-five index cards in a small cabinet. "Every morning he'd pull a card and hand it to you," Schafer remembers. "One day you're changing spark plugs. The next day, oil filters."

It was entirely time-based maintenance. Engines were torn down for major overhauls every 25,000 hours whether they needed it or not. The system worked most of the time, but it was highly inefficient.

Learning to Read the Signals

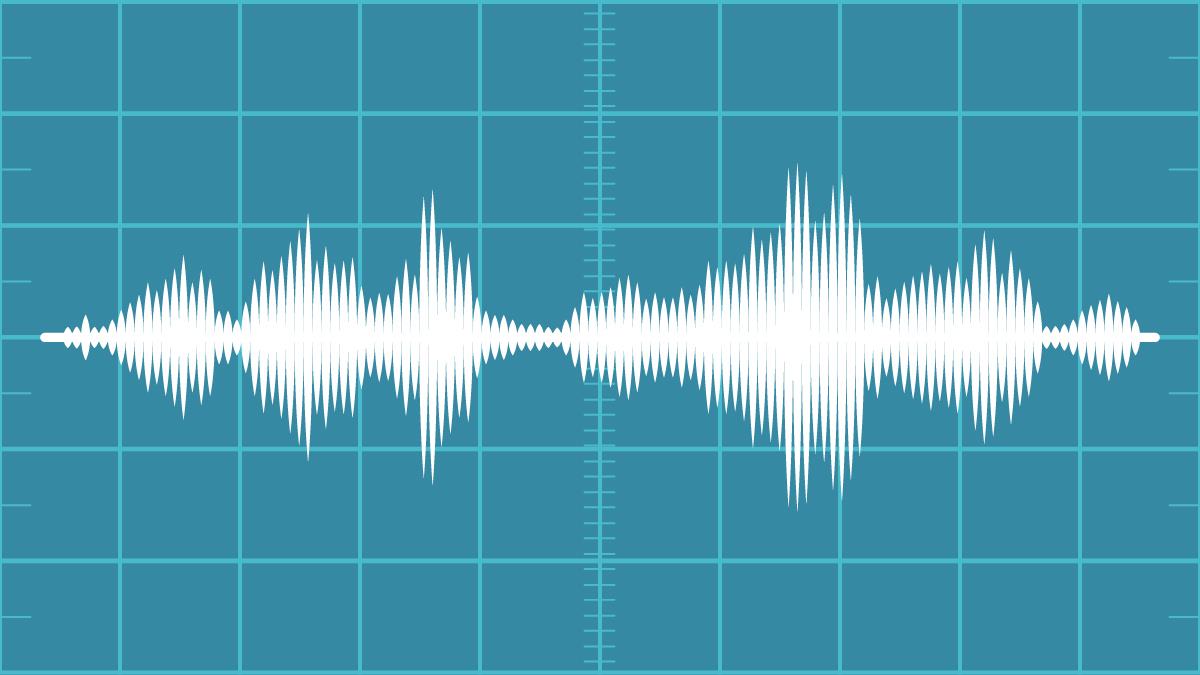

Schafer's transformation from mechanic to analyst began in 1987 when his company started using engine analyzers (a type of oscilloscope) connected to engine flywheels. These devices could show vibration and pressure traces for a single engine revolution, revealing what was happening inside the engine’s cylinders.

"It had a grid on it, and you could see one complete revolution," Schafer explains. "Instead of seeing a machine running at 250 RPM as a blur, I could determine exactly what was wrong."

But few knew how to read the patterns on the screen. "One guy told me, 'We can find a valve or two every now and then, but mostly it's guesswork.'"

Schafer refused to accept that. He studied every signal variation. "Everything was on there for a reason," he discovered. "The size of the signal and where it happened told you what was wrong… if you knew what to look for."

Without digital storage, Schafer documented everything with Polaroid photographs, building reference catalogs that showed normal signatures for each engine. "We'd compare pictures and say, 'This valve is getting louder. We must have a hydraulic lifter going bad,' or 'The pressure dropped. We're losing compression.'"

.jpeg)

Proving the Business Case

The technology showed promise, but Schafer knew he needed to prove its value in dollars if he wanted the program to continue. His company required monthly reports showing the financial impact of problems the analyst program found.

"Every month we had to send a report to our manager," Schafer explains. "If ignition timing was off by two degrees, it was causing X percent extra fuel cost. If a fuel valve was going bad, it cost us more fuel gas. We proved ourselves with dollars."

The reports were specific and undeniable. After eight to ten years of documentation, the data showed the program more than paid for itself. This business case approach became crucial as the program expanded to ten analysts covering about 100 facilities across 13 states.

"You've got to show them the money," Schafer emphasizes. "Management needs to see ROI, not just technical data."

Winning Over the Skeptics

Not everyone welcomed the new approach. Some station supervisors pushed back. "They'd say, 'We'll run our engines. Yeah, you do your little test and go on,'" Schafer recalls. Others were more openly hostile.

The real test came from the repair crews themselves. When Schafer diagnosed specific bearing failures deep inside engines, mechanics would deliberately try to prove him wrong. "They'd take that bearing straight to the shop and cut it open," he says.

Using spectrum vibration analysis, Schafer could pinpoint exact failure modes. "I could tell them the outer race of that bearing has a pit in it," he explains. The bearing would be running at 5,000 RPM, invisible inside the engine. "Every time I made a call, pit on the inner race, outer race, one bad ball…I was right every time."

Those opened bearings built his credibility over time. "They'd cut it open and say, 'Yep, he's right.'" A job that once took two weeks to do an entire rebuild now took four hours since they knew they only needed to replace one bearing.

The lesson for today's reliability professionals? "Let the data speak," Schafer advises. "Don't just tell them something's making noise. Anyone can hear that. Tell them exactly what's wrong and where. When you're consistently right, skeptics become believers."

When Prevention Entered the Conversation

The shift to digital oscilloscopes in the early 1990s changed everything again. "I could store traces on my computer and overlay them to see tiny changes over time," Schafer says. This enabled even more effective predictive maintenance, since Schafer could spot problems long before they caused failures.

The results were dramatic. Engines that once needed major overhauls every 25,000 hours now ran 100,000 to 130,000 hours between overhauls. "We don't do time-based overhauls anymore," Schafer explains. "We wait until the analyst looks at the data and says we need to do work."

One breakthrough came from observing carbon buildup during teardowns. "When you pull apart a power piston, you'll see carbon around the rings," he notes. "My thought was: if you have carbon, you have too much oil."

Over two years, Schafer cut lubrication rates by 30% from manufacturer recommendations on four engines. The result? Those engines ran another 25 to 30 years. "When they pulled them, they were clean as a whistle. No carbon buildup. No excessive wear. They just ran forever."

This approach was later scaled to a project covering 135 compressor units, reducing lubrication by 90%. After 3.5 years, the units had eliminated 90,000 gallons of oil contamination in pipelines. Compressor valve failures dropped 44%. One downstream customer saved $120,000 annually in reduced filter changes.

But Schafer emphasizes a critical prerequisite to this type of result: "You've got to be sure of what you're putting in. If you don't have a good system with accurate counters, you'll tear something up. When the count says you're putting in 10 pints a day, that's exactly what you need to get."

Building the Next Generation

Schafer's initial success required leadership support, which he later paid forward. "My tech manager told me, 'The engine will let you know when you've gone too far,'" he recalls. "A lot of people didn't have that backing. If they tore something up, they faced threats of being fired."

When Schafer moved into leadership, he adopted that same philosophy. "I'd tell guys, 'Don't just do it the way we've always done it. What can we do that makes it better?'"

His approach to training came from his own early experiences. "When I first started, I was inside a fence at a compressor station. Some guys were willing to share their knowledge. Others were afraid if you learned anything, you'd take their job—that old mentality."

By the time Schafer became a system-wide analyst, he had access to outside training and conferences. "You'd go to a week-long conference and just get overwhelmed," he remembers. "But if you pick up just one idea, that's fine. The key is you've got to come back and practice it. If you don't use what you learned in your daily work, it's not going to do any good."

For 37 years, Schafer volunteered his time to industry education, including serving as chairman of the Eastern Gas Compression Roundtable for three years. His leadership style focused on pulling quiet experts into conversations. "You've got really smart people who just sit in the crowd. Nobody knows it," he explains. "I'd contact these people and say, 'Just tell us what you did on this one project. You don't need a formal presentation. Just step up and share.'"

The results often surprised the presenters themselves. "Once you get up there and do it once, get a little confidence, it gets easier every time," Schafer notes. "A lot of people just need that little push to take that first step."

The Career-Long Lesson of Patience

When talking about his success, Schafer returns to one theme again and again: patience. "Young professionals today want to know what's next before they ever get started," he observes. "I had one engineer who'd been with us two weeks and wanted to do everything I'd done over 45 years by next year."

His advice is direct: "Learn what you're doing now before you worry about the next job. It took me 40 years to become a manager. Master this job first. It will make the next one even easier."

But Schafer also pushes back against the idea that experience alone means expertise. "We don't know everything," he admits. "Just because someone's older doesn't mean they know everything. There's new technology, new equipment."

He frames progress as building blocks. "Everything we have now was built on the backs of other equipment and other generations. If you're trying to step over that, you're going to miss something." At the same time, he warns against blind faith in conventional wisdom: "Don't take everything as gospel. Do your own research. They may not have had the tools then to prove what you're saying now."

Mountains, Motorcycles, and the Road Ahead

These days, Schafer consults selectively through Black Rock Resources, taking on training projects and compressor troubleshooting when interesting opportunities arise. But he's stepped away from the 120°F engine rooms he spent a lot of his career in.

Instead, you'll find him cruising highways on his Harley-Davidson, riding his dirt bike, or exploring muddy trails through the Appalachian Mountains in his side-by-side near his Huntington, West Virginia home.

For maintenance and reliability professionals early in their careers, Schafer's journey offers lessons that transcend specific technologies. Whether working with index cards or AI-powered systems, the basics remain the same: curiosity, careful documentation, willingness to challenge assumptions, and patience to let expertise develop.

"I always approached it like a prospector panning for gold," Schafer reiterates. "I wanted to find something interesting every time. Sometimes you'd spend half a career working on one thing that nobody had seen before." He pauses, then adds: "It's been pretty cool."

In an industry chasing the next breakthrough, Schafer's career reminds us that the most valuable innovations often come from someone willing to look more carefully at the signals everyone else dismisses as noise and patient enough to understand what they're really saying.

You can connect with Keith on LinkedIn.